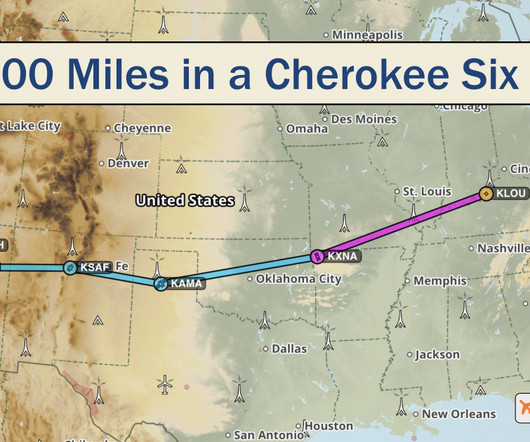

2700 Miles in a Cherokee Six

AeroSavvy

AUGUST 20, 2021

I’m not Lindbergh… This trip was ambitious for me, but quite common in the general aviation community. I spent a few months researching aircraft performance and high altitude airport flying techniques. As altitude increases, air molecules spread out, resulting in less power and lift.

Let's personalize your content